Have you ever heard of hardy passion fruit? Probably not. When you think of passion fruit, you tend to think of truly tropical fruits from South America. And that is true. The passion fruits of the species Passiflora edulis available in supermarkets are tropical plants, just like the majority of the more than 600 species of the genus Passiflora.

Have you ever heard of hardy passion fruit? Probably not. When you think of passion fruit, you tend to think of truly tropical fruits from South America. And that is true. The passion fruits of the species Passiflora edulis available in supermarkets are tropical plants, just like the majority of the more than 600 species of the genus Passiflora.

The plants of the genus Passiflora are also called passion flowers and over 100 species of them produce edible fruits. These fruits are very different and often look quite different from the familiar passion fruit. They range from the huge fruits of Passiflora quadrangularis, which can be up to 30 cm in size, to the marble-sized fruits of Passiflora foetida. In terms of colour, you will find everything from green to yellow or red to black, and in terms of taste, the edible berry fruits range from pineapple to...garlic! So there is a lot to discover. By the way, if you would like to plant a passion flower in the garden yourself, you can buy three different passion flowers in the Lubera Garden Shop.

Table of contents

- Are there any winter hardy passion flowers and where do they come from?

- How does one come up with the idea of breeding hardy passion fruit?

- From thought to action: the breeding begins

- Why Passiflora incarnata is the perfect candidate

- What are the breeding goals with Passiflora incarnata?

- Difficulties in growing Passiflora incarnata in Europe

- How can we adapt Passiflora incarnata to our climate?

- And what about the flowers and fruit of the passion fruit?

- Self-fertility or how to make babies alone

- The next step: interspecific hybrids

- Which Passiflora species are suitable for hybridisation?

- Interspecific hybrids: easier in theory than in practice

- Passion fruit like tomatoes or Physalis: annual passion flowers as an alternative

- And was that all?

Are there any winter hardy passion flowers and where do they come from?

But the question arises: are there any frost-tolerant and hardy species among the passion fruit plants at all? Fortunately, yes! On the one hand, there are the two species Passiflora incarnata and Passiflora lutea from the United States, which can withstand winters below - 20°C there.

Picture: Passiflora incarnata - the robust passion fruit that is hardy down to -20°C.

Then there are the species of the Tacsonia group among the passion flowers, which grow in the Andes at altitudes of up to over 4,000 metres. There, some of these species are often exposed to freezing rain, snow and sleet showers and they still bloom with fantastic, pink flowers that are pollinated by hummingbirds.

The last interesting region for hardy passion flowers has turned out to be Argentina and the south of Brazil in the mountainous regions of the Atlantic rainforest. The well-known blue passion flower Passiflora caerulea, for example, comes from this region.

Picture: Passiflora caerulea - stunning flowers from the tropics with cold tolerance.

How does one come up with the idea of breeding hardy passion fruit?

How do you get the somewhat crazy idea of breeding hardy passion fruit? I was training to be a gardener in 2011 when we were given various passion flowers to sell in my training company. And as you do when you are an apprentice gardener, I cut a few cuttings and rooted them at home.

I was immediately enraptured by the impressive exotic flowers. A year before, I had already successfully grown a passion fruit plant from the seeds of supermarket fruit. Now a wall of passion flowers was overgrowing the terrace of my parents' house and I thought to myself: 'A hardy passion fruit would already be a perfect plant...Beautiful, decorative foliage, large exotic flowers, plus perhaps the best fruits of all, and all this combined in a plant that also survives in our garden north of the Alps.'

From thought to action: the breeding begins

In the years that followed, my passion for passion flowers always accompanied me but often led to a marginal existence. It wasn't until I started my horticultural studies in Geisenheim, Germany in 2018 that the topic really took off again. I thought to myself, 'If you really want to plant hardy passion fruit, you can't hope that someone will grow them for you. You have to do it yourself!'

So I used the following studies to learn as much as I could about Passiflora, researching this genus and also growing the plants. Thanks to a nice lady who put her garden at my disposal, I was able to test and cross about 70 plants under outdoor conditions. All this led to the fact that in the end I even wrote my diploma thesis on the topic 'Breeding hardy passion fruits'. I later compiled all my knowledge into a 140-page book, illustrated it with many pictures and published it.

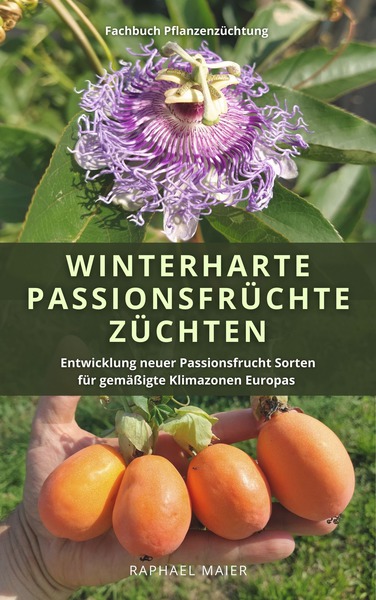

Picture: The book 'Winterharte Passionsfrüchte züchten' (Breeding hardy passion fruits) by Raphael Maier.

But enough about me now. What does my actual breeding work at Lubera look like and what new hardy passion fruit varieties can you look forward to soon?

Why Passiflora incarnata is the perfect candidate

At the moment, I have concentrated on the species Passiflora incarnata when it comes to hardy passion fruit breeding. Why? On the one hand, this plant probably has the best absolute winter hardiness. On the other hand, this species was already eaten and even cultivated thousands of years ago. When the first Europeans settled in what is now the United States, they also encountered Passiflora incarnata.

The famous Captain Smith, who founded the English Jamestown colony, reports in his diary that the native Powhatan tribe grew passion fruit, and even on the palisade of the colonists' wooden fort the plant grew. Archaeological evidence shows that maracock (as the natives called the fruit) was consumed and cultivated in almost all Native American settlements in the southeast of what is now the United States. Unfortunately, with the decline of the North American Indians, the cultivation of this great passion fruit has also fallen into oblivion and is only occasionally picked by true connoisseurs as delicious wild fruit.

What are the breeding goals with Passiflora incarnata?

At the moment, the purple passion flower (Passiflora incarnata), is a wild plant. Therefore, it must first be domesticated (again). In the process, various screws have to be turned at the same time in order to turn the wild plant into a cultivated species. Perhaps the most urgent issue is climate adaptation. Maracock is adapted to the climate of the southeastern United States. There, although winter temperatures can be as cold as - 20°C or lower, the summers are also very hot, with more than two months above 30°C. And that is exactly what we hardly have so far, despite climate change, and that can lead to difficulties in growing the Incarnata passion flower.

Difficulties in growing Passiflora incarnata in Europe

Maypop, as the plant is also called in the United States, grows as a perennial. Every year in the winter, the above-ground part dies and in the spring, the plant sprouts again from the root rhizomes. In this way, the actually subtropical plant hides in the ground from the snow and cold. In itself, this is an ingenious system; the only problem is that our passion flower is used to an American climate and needs quite high temperatures for resprouting. As a result, in some parts of Germany, the shoots do not emerge until June or even later. This gives the poor passion fruit hardly any time to form enough new foliage, to flower and to produce fruit.

The second problem is again related to our cool summers. Often the fruits do not ripen in our region, they simply take too long from flowering to ripening and if there is cold weather again, then the whole process takes even longer.

How can we adapt Passiflora incarnata to our climate?

How can we solve these problems now? This year I have sown about 1200 different seeds of Passiflora incarnata. A good part of these seeds come from plants growing on the northern edge of the natural range: from Illinois, Delaware, Pennsylvania and New Jersey. These plants should also tolerate less heat and have a shorter growing cycle than passion flowers from the southern United States.

Pictures: The Passiflora seedlings are planted out on the Lubera trial field in Buchs, Switzerland.

Next spring, we hope to be able to select individual plants from this population that sprouts unusually early and then also find plants in autumn whose fruits ripen reliably in Switzerland.

At the same time, I am working on another long-term solution. For this, I am trying to cross other Passiflora species with Passiflora incarnata. One example is Passiflora tucumanensis from Argentina. The aromatic fruits of this passion flower species only need one month to ripen and can thus significantly shorten the typical ripening time of three months for Passiflora incarnata. Other species, which can also be crossed, have a much lower heat requirement, so with a little luck, we may have a winter hardy passion fruit variety in the not-too-distant future, which will also ripen reliably in cooler regions.

And what about the flowers and fruit of the passion fruit?

The climate adaptation of the passion flower is important, but no one buys a plant just because it grows well in our climate. The purple passion flower has great big exotic flowers and even without fruits, it is an exceptional ornamental plant. In our breeding garden, we already have different varieties with white, pink and purple flowers. In the summer, we will select plants that are particularly eager to flower and are characterised by their beautiful and large flowers.

Picture: A selection of different coloured Passiflora incarnata flowers from Raphael Maier's breeding garden.

The fruits of the wild 'Maracock' are usually about 25 to 30 g in weight; they are sometimes only partially filled and have a white flesh (meaning the aril around the seeds, which is eaten) and they are very variable in taste. In recent years, I have already managed to create a large-fruited variety through cross-breeding, which consistently makes fruits from 70 g to 95 g. Now we are looking for exceptionally tasty fruits, which ideally also have a nice yellow flesh.

Picture: The cut open fruits of Passiflora incarnata.

Picture: The fruits of this large-fruited Passiflora incarnata variety weigh between 70 and 95 grams.

Pictures: More different passion fruit varieties from the breeding field.

Picture: The refractometer can be used to measure the sugar content in the fruit.

Self-fertility or how to make babies alone

An important issue is the self-fertility of the maypop. Passiflora incarnata is much like us humans in that it needs another partner to make babies (in this case fruits). However, unlike humans, we would like this not to be the case. So even with just one hardy passion fruit plant in the garden, you could harvest lots of passion fruit. To make this possible, we are hand-pollinating 700 different Passifloras this summer to see if any are out of line and self-fertile thanks to a lucky mutation.

Picture: A net is placed around the crossed flower to prevent it from being pollinated by insects.

The next step: interspecific hybrids

Many of our cultivated plants are actually crosses of different species. Wheat, for example, is a hybrid of three different species. Such interspecific hybrids have the advantage that they can combine the positive characteristics of different plant species in just one plant. Passiflora incarnata can do a lot, but not everything. This is where such interspecific hybrids can help out. For example, one Passiflora can contribute winter hardiness and fruit colour, another species can contribute taste and a third species can contribute disease resistance and flowering readiness. For this reason, I am also working on complex hybrid passion flowers.

Picture: A Passiflora hybrid from the breeding of Raphael Maier.

Here, the genus Passiflora has the advantage over many other plant families in that the individual species can often be crossed relatively easily and that hundreds of such hybrids already exist.

Which Passiflora species are suitable for hybridisation?

For our goal of hardy passion fruit, I use the following passion flower species, among others: the already mentioned Passiflora tucumanensis, which is almost as hardy as Passiflora incarnata, and moreover has wonderful nodding flowers; the well-known blue passion flower Passiflora caerulea, which has the invaluable advantage of being very adaptable and does not freeze above ground in the winter; Passiflora cincinnata with its impressive, purple flowers, very good drought resistance and very aromatic fruits; Passiflora mixta, Passiflora insignis and Passiflora pinnatistipula from the Andes of South America, which are excellently adapted to cool and rainy weather in Germany or Switzerland; and last but not least, of course, the well-known passion fruit plant Passiflora edulis, which is appreciated worldwide for its delicious fruit.

Picture: Passiflora caerulea despite the frost.

Interspecific hybrids: easier in theory than in practice

When creating such new 'mixed species', one inevitably encounters a multitude of problems: some species just don't want to be crossed and you have to use a lot of tricks to overcome these barriers. When the cross has been successful, it often happens that the seeds do not germinate or produce crippled plants. When the plants do grow nicely, they are often partially sterile or produce almost empty fruits. All this can sometimes be frustrating, but every now and then you are rewarded with an exceptional plant. I now have a few hybrids of three to five species, which have other advantages than Passiflora incarnata: shoots that do not freeze back in the winter or underground and sprout again from the old wood; larger flowers; fruits with yellow skin, different flavours, etc.

Picture: The test plant of Passiflora hybrids.

Passion fruit like tomatoes or Physalis: annual passion flowers as an alternative

But do passion fruit plants really have to be hardy? Of course, you can also grow a passion fruit plant in a container, which produces delicious fruit, but then you have the problem of overwintering. But how about growing passion fruit like tomatoes or cucumbers or Physalis? You grow Passiflora plants from seed in the spring (or buy ready-made seedlings later) and plant them in the garden starting in mid-May. They then flower and fruit throughout the summer, and in late autumn the passion fruit plants are removed again.

But is that possible at all? Yes, there are various species of passion flowers such as Passiflora foetida, Passiflora ciliata or Passiflora arida, which produce small, tasty fruits (about the size of date tomatoes). The beauty of these species is that they are absolutely self-fertile, so you only need one mini passion fruit plant. In outdoor trials in 2019 in Hesse, Germany, I was able to harvest up to 100 small passion fruits per plant on some varieties. This year, we will repeat the field trials and test different varieties and species in order to find the most suitable candidates for your garden.

Picture: The fruits of one-year-old Passiflora foetida plants.

Picture: The beautiful, white flower of the Passiflora foetida is pollinated by a bee.

And was that all?

As you can see, the world of passion fruits still has a few surprises in store for us and hopefully also for you. The theoretical possibilities for hardy passion fruit are almost inexhaustible! There is certainly no lack of ideas and plans, but only time will tell what can be realised.

Picture: Is this the future of passion fruit cultivation?

If you would like to learn more about the exciting topic of growing hardy passion fruit and learn some of my secrets, you are welcome to buy the book on the subject.