Tomatoes are a good example of how breeding vegetable varieties for the garden works. Breeding is actually easy, but it takes a lot of perseverance and above all continuity until you can finally bring a variety onto the market after six to ten years. In the following, I will briefly explain what is involved in our outdoor tomato breeding programme and how we specifically bred the Happy Black® variety.

Tomatoes are a good example of how breeding vegetable varieties for the garden works. Breeding is actually easy, but it takes a lot of perseverance and above all continuity until you can finally bring a variety onto the market after six to ten years. In the following, I will briefly explain what is involved in our outdoor tomato breeding programme and how we specifically bred the Happy Black® variety.

Variety testing and selecting parent varieties

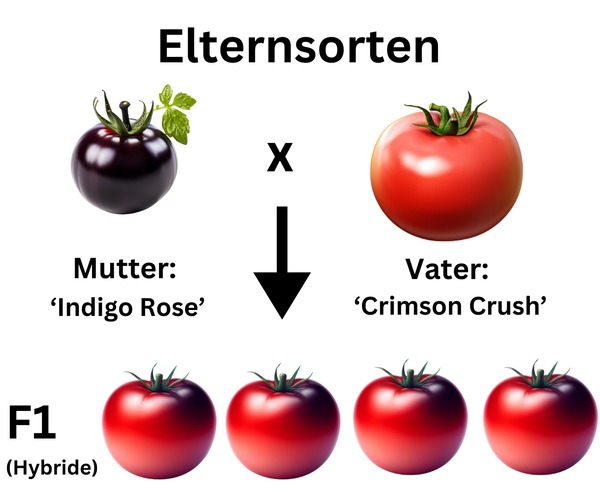

Every year we test several dozen new varieties from all over the world that claim to be particularly robust and resistant to late blight, i.e. our main diseases Phytophthora infestans and Alternaria. The salad/beef tomato Crimson Crush and Indigo Rose stand out positively.

The tomato variety Crimson Crush originates from England, was bred by Simon Crawford and has a so-called Ph1,2,3 resistance. When tested in Buchs, Switzerland, the outdoor resistance in the open field is slightly below our desired level, but is of course significantly better than known standard varieties. Like the entire Indigo variety group, Indigo Rose was bred by Jim Myers, a professor at Oregon State University. The Indigo variety group is characterised by an unripe fruit skin that is often blue in colour and black-red when ripe. Jim Myers crossed a wild tomato species collected in the Galapagos and in Chile in the 1960s with cultivated varieties. The wild variety is primarily responsible for the blue-black skin, which in turn is due to its high anthocyanin content. Typical of black tomatoes is also the sour, refreshing flavour, combined with a special spiciness (which flavour specialists identify as umami). Older 'black' varieties such as Black Krim have a different genetic background, their blackish or greyish skin is caused by a pigment called pheophytin. What we also noticed in our trial with Indigo Rose was this: although the black American varieties from Oregon are not absolutely resistant, they do last significantly longer than the standard varieties. This gave rise to our breeding idea: we would like to increase resistance to Alternaria and Phytophthora by crossing the two varieties and, of course, at the same time introduce the black-red anthocyanin colour into the resilient outdoor tomatoes.

Crossings

We also make new crosses every year to ensure a full pipeline in variety development. With these basic crosses, we try to look 10 years into the future: what characteristics must outdoor tomatoes have in 10 years' time if they are to be grown successfully in the garden and on balconies and terraces? However, the sine qua non for all our outdoor tomatoes is extensive resistance to early blight (Alternaria) and late blight (Phytophthora infestans).

For crosses, we select two very good parent plants with different characteristics, in this case Indigo Blue and Crimson Crush. Both have good, but not quite sufficient resistance; here we want to combine and amplify their two resistances. And yes, of course we are interested in the black colour and high anthocyanin content of the Indigo tomatoes. For the cross, we remove the pollen carriers of the mother variety Indigo Rose [to avoid self-pollination] and transfer pollen from the male parent variety using a brush. It is also possible to simply pick a fully bloomed flower or one that has almost finished blooming and use it to fertilise the pistil of the mother variety directly. The pollen then germinates on the stigma of the pistil and fertilises the female organs of the flower. The fruits produced from the artificially fertilised flower are harvested, the seeds are extracted and hardened and sown the following spring. This produces the first filial generation F1.

F1 generation

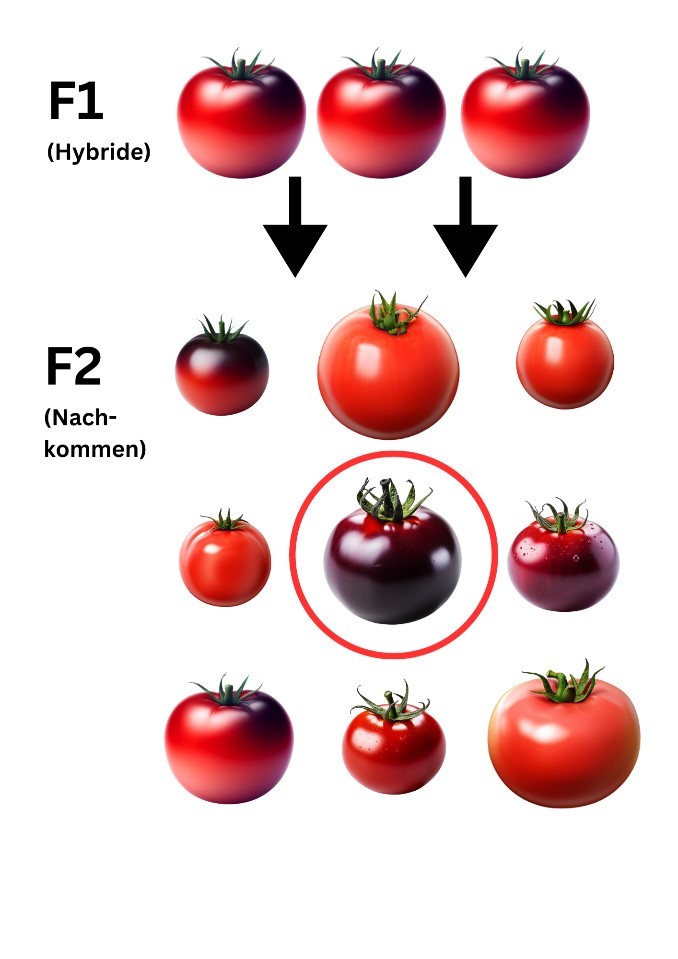

Oops, what's happened there? Although we have bred two very different varieties, the resulting seedlings look almost identical. At best, a slightly dark veil on the tomato fruit (close to the fruit stem) indicates that a black variety could be involved here. What happened? By crossing two open-pollinated varieties, we have done nothing other than produce an F1 hybrid that produces very similar seeds and daughter plants. This also makes it clear that the breeding of new open-pollinated varieties often starts with F1 hybrids that are produced involuntarily in the first generation. Despite the similarity of the tomato varieties in the F1 generation, we also select the two or three most beautiful plants, harvest fruit from them again and dry the seeds.

F2 generation

Only now does the crossing really become a reality. In this second generation (F2), the hybrids are split and now all the shades between the parent varieties are revealed. Now we mainly select the varieties that also show as much black as possible on the fruits, but we also focus on selecting the most resistant plants that combine the two obviously different resistances of the parent varieties and achieve the overall goal of 70% green leaves at the end of the growing season.

Production of inbreeding lines

In the second filial generation (F2), we have selected the most resistant and blackest tomatoes, which also do not burst, taste good and grow as strongly as possible. We harvest one fruit from each selected tomato plant and sow the seeds again next year. Due to the pollination biology of the tomato, we can be sure that the flowers are almost 100% self-pollinated (i.e. by pollen from the same plant). This is simply due to the fact that in most tomato varieties the pistil no longer grows out of the cone of the anthers covering it, or only grows out very late, so it offers no landing surface for foreign pollen. By the time the pistil grows out of the anthers and is therefore accessible to foreign fertilising pollen and pollinating insects, it has long since been pollinated by the pollen of its own plant. It is therefore no longer necessary to additionally protect the line plants from cross-pollination.

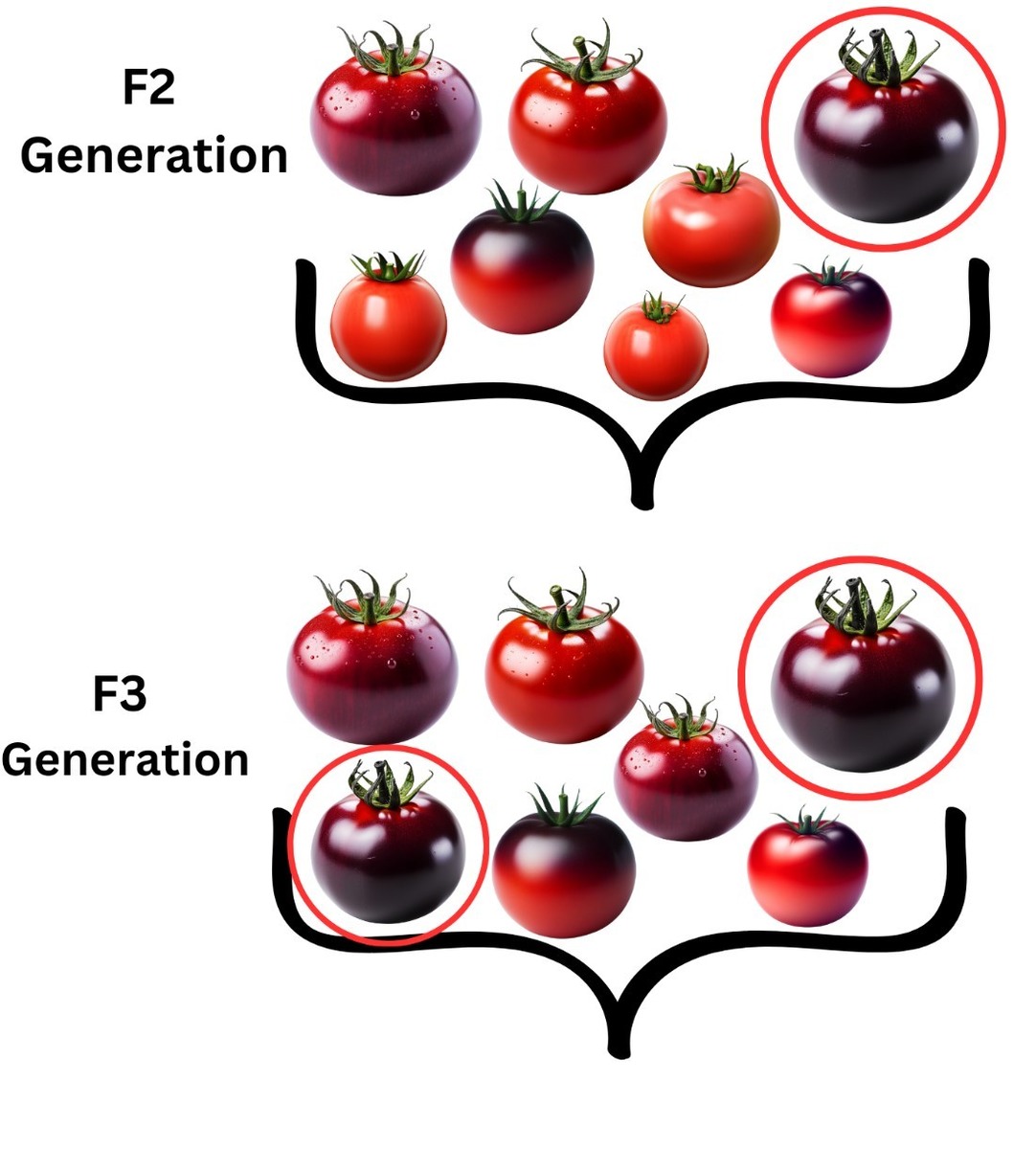

Development of the inbred lines F3 to F9

The process is now repeated every year. We plant 10-30 plants from the seeds taken from a line and then select the best one to three individual plants from these again and again. In order to prevent the number of varieties and lines to be tested from growing to infinity, lines that are inferior to other lines overall or in a specific attribute are of course also sorted out each year. When breeding Happy Black®, many lines were eliminated in the end due to insufficient disease resistance and others were not fertile enough; finally, we also favoured breeding lines whose fruits are more resistant to bursting in rain and moisture.

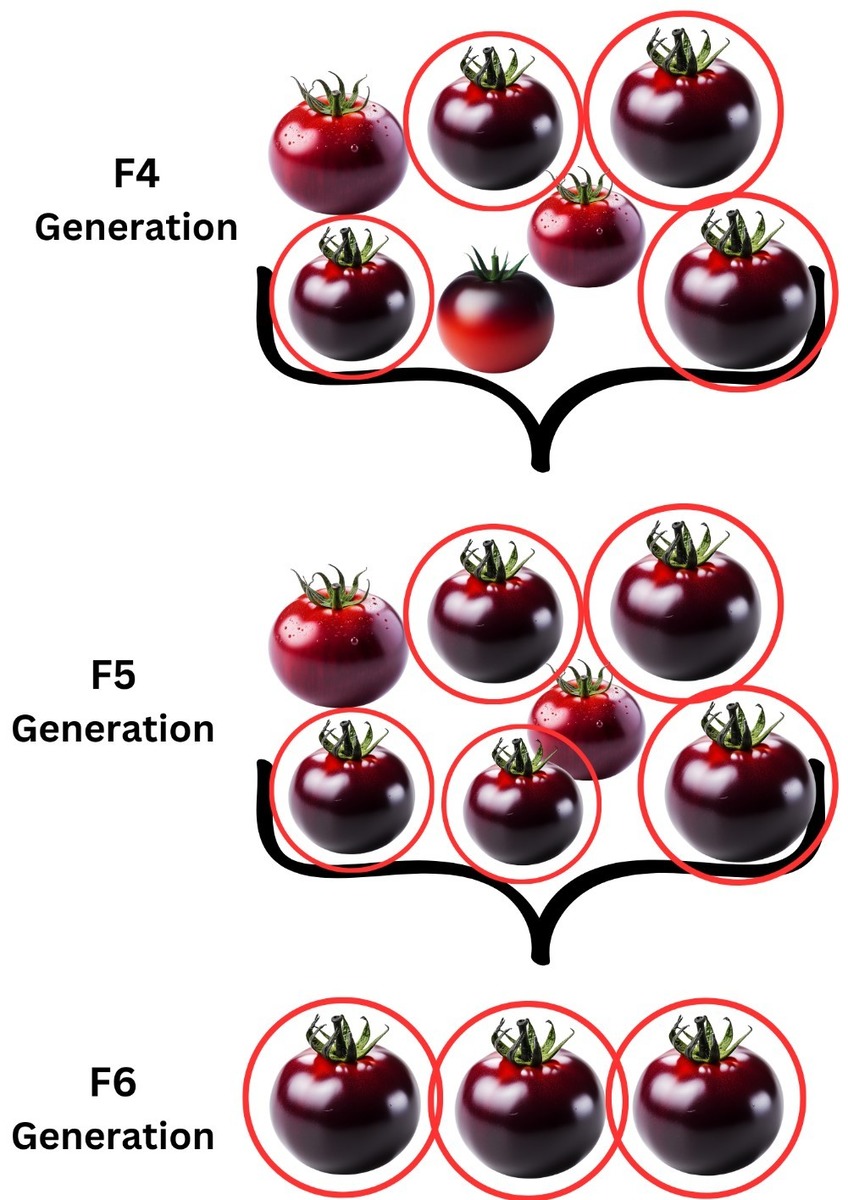

The tomato fruits and plants become more uniform from generation to generation through self-pollination and inbreeding (see picture), until in the end (as far as possible) all plants have the desired characteristics and all look the same. The desired stability and the ability for the seed to breed true is largely achieved after six generations, but one often goes as far as F8-9 to ensure even greater homogeneity of the daughter plants.

At the end of such a multi-year selection process, you often still have several lines in parallel and then have to decide which one will definitely become an open-pollinated variety. It is also quite possible for two or more varieties to emerge from a cross. The same could happen with the cross between Crimson Crush and Indigo Rose, which has so far produced Open Sky® Happy Black. We are still testing a special line from the same cross that grows somewhat more compactly and is also suitable for growing as a vine tomato. Let's see if the line will ever become a variety...

Selection criteria

In general, it must be said that the selection process in vegetable breeding must always be very strict because we can only compensate for and combat the negative side effects of inbreeding (signs of degeneration, weak growth, declining health) through extremely strong selection pressure (the rigorous discarding of all plants with undesirable characteristics). In tomato breeding, resistance to Alternaria and Phytophthora is always at the centre of our Open Sky® field breeding and must be present in every variety. Part of the resistance is also based on strong shoot growth, so we always tend to favour the stronger growing lines (in the case of vine tomatoes). Then comes the taste, the firmness of the fruits, which are to be cultivated outdoors, and finally the shape, colour and size. In 10 to 20 years' time, we would like to offer a comprehensive range of outdoor tomatoes with as many different fruit and plant types as possible.

Maximum disease pressure in open field breeding

All of our tomato breeding from the crossing stage (which is carried out in the greenhouses at our Lubera® breeding centre in Buchs, Switzerland) takes place outdoors. Potential variety candidates are therefore always exposed to outdoor stress and natural weather conditions for six to ten years. A new variety or variety line first has to survive this. Open Sky® Happy Black has certainly passed this endurance test. That in itself is a huge difference to industrial tomato breeding, which primarily takes place in greenhouses and ultimately leads to varieties that are intended for protected cultivation in greenhouses. Our breeding location in the St. Gallen Rhine Valley is particularly well suited to this, as we record up to 1300 mm of rainfall per year, with a good proportion of this rain also falling during the growing months. As a result, the weather conditions are also ideal for the most important fungal diseases of tomatoes, Phytophthora and Alternaria, meaning that our breeding plants are exposed to maximum disease pressure.

Figures with regard to tomato breeding

Every year we plant the following for outdoor tomato cultivation alone:

- 5000 tomato plants in total

- Approx. 150 inbred lines for variety development

- Approx. 30 advanced inbred lines in commercial status or close to it

- 15-20 crosses in plant quantities adapted to the crossing objective