Unknown or little-known, hardly noticed fruit species are also worked on in the Lubera breeding programme. But why do we care about the obscure, little demanded, often not directly edible berry and fruit species, when we could possibly invest more in raspberry breeding? In this article, Markus Kobelt shows the importance of wild fruit species in the Lubera breeding programme and also describes in concrete terms the objectives for which research is carried out on the various wild fruit species.

Unknown or little-known, hardly noticed fruit species are also worked on in the Lubera breeding programme. But why do we care about the obscure, little demanded, often not directly edible berry and fruit species, when we could possibly invest more in raspberry breeding? In this article, Markus Kobelt shows the importance of wild fruit species in the Lubera breeding programme and also describes in concrete terms the objectives for which research is carried out on the various wild fruit species.

The portfolio approach

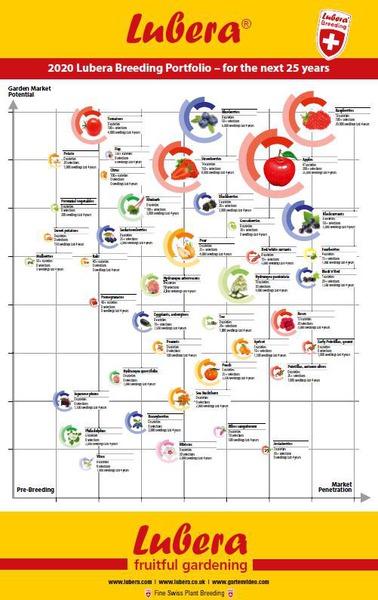

Breeding at Lubera follows a distinct portfolio approach. Perhaps in the same way as one would put together a stable and promising equity basket, we select our breeding projects. At the beginning of a project, which can take 15 or 20 years, it is far from certain how successful the breeding will be, how quickly we will make progress and how fast we will be able to bring specific varieties to the market. And so we start and maintain a considerable number of large, medium and also very small projects in order to always have enough new stories up our sleeve and to be able to compensate for setbacks in individual species and breeding projects. In addition, we carefully feel our way into breeding projects, especially with wild fruit: usually, we start with a collection of varieties, then a careful evaluation and sifting of the varieties, and finally the decision to start breeding ourselves, sowing seeds and/or targeted cross-breeding. This means that the effort can vary from year to year, and it is not uncommon for small projects to be abandoned altogether. On the other hand, this fumbling around can also generate good breeding ideas, i.e. ambitions that are feasible from a breeding point of view and concepts that can possibly significantly change the characteristics of the fruit species for the gardener. In the best case, an ugly duckling becomes a beautiful white swan.

Picture: Overview of the current Lubera® breeding programmes

What is wild fruit?

When we talk about wild fruit breeding, it is necessary to define the term at least to some extent. It refers to fruit and berry species that have only been domesticated to a small extent and have not yet been cultivated or not cultivated very intensively. In most cases, they are not particularly important on the fruit market, in the garden or even in commercial cultivation, and very often there are good reasons for this: in many cases, wild fruit species are not directly edible, which of course limits their attractiveness for the market and for the gardener; many times they have other negative characteristics, such as thorns or spines, bitter fruits, insufficient climate adaptation and so on.

Why growing wild fruit is interesting?

But why should we bother breeding such ugly ducklings now, when there are enough white swans that can be made even whiter? Exactly for this reason: it is neither easy nor very effective to make white swans a little whiter. Conversely, very great progress is possible with many wild fruit species, and that with a relatively small and limited input – not because we are particularly clever breeders (of course we are😉), but because not very much has been bred on these species yet. Within our portfolio strategy, wild fruit breeding would therefore be betting on a share that is completely insignificant and costs almost nothing, but which may one day experience an extreme increase in value. To put it even more generally: only a very small part (less than 10%) of the basically edible plants has been domesticated and/or cultivated. It is reasonable to assume that there are still many undiscovered treasures, both for the garden and for commercial cultivation.

An example of wild fruit breeding: the cultivated blueberry

Picture: Blueberry in its natural habitat

The finest historical example of successful wild fruit breeding is a soft fruit star of the present day: the blueberry. It is in the process of overtaking the raspberry/blackberry as the world's second most important type of soft fruit – and in my opinion it has a good chance of one day also replacing the strawberry as the soft fruit leader. It is hard to believe, but the blueberry as a domesticated, cultivated blueberry is barely 120 years old. It was only at the beginning of the 20th century that researchers at the USDA very slowly began, at first only with small trials and with wild selections, to improve the North American Vaccinium species that had previously only been collected wild in the eastern states of the United States. Yes, you have understood me correctly: we hope, of course, to find a new blueberry at some point in our wild fruit experiments and thus launch a similar career😉. After all, the example of the blueberry reveals decisive criteria for a future berry or fruit star: a wild fruit with a very substantial possible future should probably tend to have the following characteristics:

- Easy to cultivate (but this is actually not the case with blueberries)

- Directly edible

- Everybody's darling, i.e. does not have any special characteristics, no aggressively preferable flavours, etc.

- Sweet (all or most consumers are oriented towards more sugar)

- High-yielding

- Good for picking

- Can be stored and transported as well as possible

- Can also be grown in the southern hemisphere, so that a year-round supply can be ensured in the longer term

So you see, these are rather ambitious goals and you and we will find some criteria in every project that our new soft fruit varieties cannot fulfil in breeding. It also makes little sense to always focus only on these criteria when working with new fruit varieties – since the success factors are always put together individually. But one thing is certain: some of these criteria must certainly apply for a successful type of soft fruit.

Informal start and rapid progress

The historical example of North American blueberry breeding shows some further patterns worthy of imitation, even after 120 years:

The proof of the pudding is in the eating – (almost) all breeding starts as tinkering: this is exactly how it was with blueberries. Mr Coville, who worked as an agronomist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, discovered the extensive natural blueberry plants around his holiday home in New Jersey and became more and more interested in them. Where do these plants grow, what kind of soil do they need, what are the conditions for pollination, how can we collect the largest fruits in nature? At the beginning, this was not an interdisciplinary research group with a budget of millions, but a group of women (Elisabeth White!) and men who were simply interested in blueberries. And with this rather informal approach they managed to influence the history of blueberries until today. Many current varieties are only two to four generations away from the collected wild fruit selections and first varieties. And despite the relatively limited effort, huge advances were possible; until the 1980s and even the 1990s, the varieties of the first breeders dominated the blueberry market.

The CI of a new variety and also a new fruit species

Nevertheless, it is useful to establish some important criteria right at the beginning: already in his first articles for the bulletin pamphlets of the USDA and in his collecting orders to local berry collectors, Coville describes the external characteristics of the blueberry that were most important to him:

- As large as possible, which has an extremely strong influence on the profitability of small fruit

- No bleeding at the stem base, which is crucial for storability and transport

- White ripening and thus a blue-light blue colour as an important external distinguishing feature of a blueberry. Due to the genetics available in the north-eastern part of the United States, it would have been quite possible to choose a purple-black colour as a standard. Sensible and clear decisions on the CI, the 'corporate identity' of a new fruit species promote its later career.

Concrete wild fruit breeding projects at Lubera

Firstberries – Lonicera caerulea

Picture: ripe first-berry fruits - Is that all this plant species has to offer?

Firstberries or honeyberries are still bobbing up and down, both in terms of the variety and the cultivation. Here we are trying to find out whether this type of berry has the potential for much more. Can we breed varieties that go towards 3-4 g, i.e. offer more juice, flesh and eating experience? And are there perhaps self-fertile varieties, since up to now two different varieties have always had to be planted for sufficient pollination? The step from non-self-fertile to self-fertile varieties is, by the way, typical for almost all domestication processes of plants. And yes, there is one last question: is there a special 'use' for firstberries, something that could distinguish them from all other fruit species? For the garden, it is also crucial to ask whether we can succeed in growing honeyberries that lose some of their growth character, which is geared to a short growing season: many especially continental Eastern European firstberries sprout very early; they bear fruit early in May or early June, and then go into autumn already in the summer, with necrotic and unsightly leaves – which is not a pretty sight in a garden.

Saskatoon berry – Amelanchier alnifolia and hybrids

Picture: Saskatoon berry in flower; a plant for the whole year with delicious fruits in summer and a striking autumn colour.

This is a typical example of a fruit species that perfectly combines ornamental value and usefulness. Now the aim is to make the fruits bigger and above all fruitier, with more sugar and more acidity. The slightly green almond flavour, which takes some getting used to, is part of the fruit type, but it should be more discreet. Above all, it is important that the fruits ripen more evenly. At the moment, it looks as if the focus is on improving the existing varieties a little bit at a time. However, there are also breakthroughs here, completely new breeding directions. We know the Saskatoon plants as big bushes, as tall as a man and even taller. But there are hybrids that grow much more compactly and are more like currants. Such Saskatoon berries are especially interesting for the garden.

Elderberry – Sambucus nigra & canadensis

Picture: Is such a flowering splendour also possible on the one-year-old shoots of the elder?

How nice it would be if elderberries would flower and ripen on this year's growing wood (and not on last year's growth). This would make a completely new cultivation possible for the garden, which would not see the elder as a dominating tree element or as part of a large wild fruit hedge, but as a small berry bush, where the utilisation of the continuous flowering is just as important as the harvesting and processing of the fruits.

Sea buckthorn – Hippophae rhamnoides

Picture: Will we be able to enjoy the ripe sea buckthorn fruit straight from the bush in future without having to grimace?

Could one also eat sea buckthorn directly, are there sweet varieties that are suitable for direct consumption? And how could one try to grow the annoying thorns out of the sea buckthorn? With sea buckthorn it would also be very important to find more self-fertile plants or rather still varieties that bear fruit parthenocarpically, i.e. without fertilisation.

Oleaster – Elaeagnus multiflora & umbellata

Picture: Pointilla® Cheriffic® (Elaeagnus multiflora) already has a certain size. Is it possible to increase this size?

Among the oleasters or silverberries, Elaeagnus multiflora is particularly interesting. It is self-fertile and already has a nice fruit size and a super exciting taste with a surprisingly early ripening in June. Is it possible here to get further with the fruit size and thus the stone/flesh ratio? Could the stone be even softer so that it can be eaten without problems? Or even smaller? These are the questions we are trying to answer here in the breeding department.

Golden currant, clove currant, fourberry – Ribes aureum & odoratum

Picture: Fourberry® Orangesse® - The coloured fruits are not yet so strongly represented among the fourberries, but that will change.

Here we see especially new colours, red and orange in the breeding pipeline, which further differentiate this small fruit species. In principle, fourberries with their strong ornamental value tend to have better prospects in horticulture than currants, but in addition to the fruit size, the plant health must also be stabilised. With Ribes aureum and Ribes odoratum there are always unexplained plant deaths, but with some selections this never happens; with others more frequently. Many red and orange fourberries are largely self-fertile. We are currently testing a large number of selections for their self-fertility and will also find something here. Because we always tend to select the most fertile genotypes in fruit selections, self-fertile varieties are indirectly favoured here, so to speak, as in other domestication processes. Self-fertile varieties are usually significantly more fertile than non-self-fertile varieties that depend on pollinator insects. They then only have to be specifically identified in the breeding material. Basically, the fourberry beats many other fruit varieties in terms of taste profile and colour versatility.

Mulberry

Picture: ripe fruits of Morus alba - don't let the name 'alba' fool you - Morus alba varieties can bear black, red or white fruits (and countless shades in between).

Is the mulberry, which has been cultivated and domesticated for 5000 years, really a wild fruit candidate? What could be insufficiently developed about this plant? It should be noted here that mulberry cultivation has not developed on its own and fruit-related, but in symbiosis and synergy with the silkworms whose preferred food it is. The focus of the 5000 years of domestication processes was not on the fruit, but above all on the leaf and ultimately on the renewable raw material. So there are endless new possibilities to develop a new fruit species for Central Europe and the North, whereby the development candidates mainly refer to Morus alba, the white mulberry, which was not originally developed for its fruits but only for silk production. Morus alba also shows a much greater diversity than Morus nigra.